As the primary tax collection agency in the country, contributing some 70% of total federal government revenue, the FBR is long-accustomed to contending with ambitious collection targets set for it by a perpetually cash-strapped government.

To meet these targets, the FBR has also received an incredible amount of support and resources through a near-continuous stream of reform and capacity-building programs. Over the years, the FBR has also spent billions on initiatives aimed at increasing documentation and oversight, with a new Rs. 41 billion digitisation project approved in May of this year.

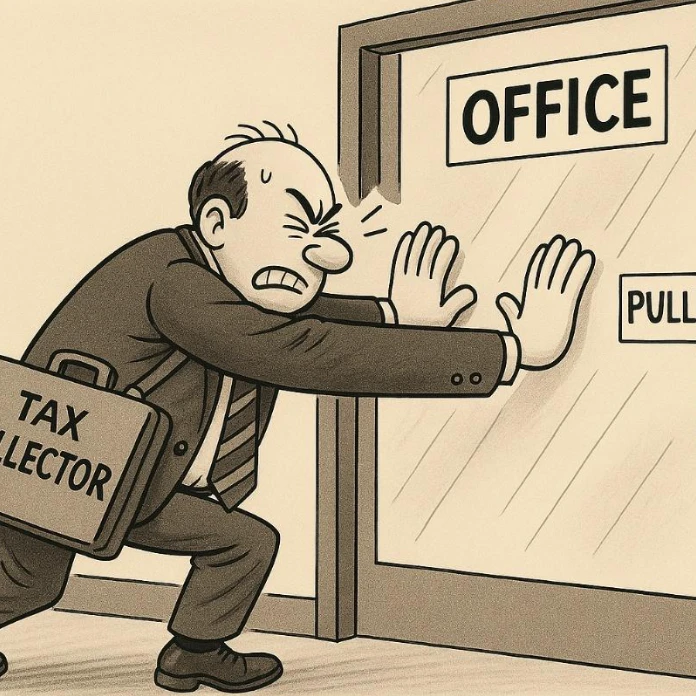

Yet, the FBR has failed to meet its beginning-of-year targets in all but two of the last fifteen years, including the last three years. Clearly, something is not working. There is no doubt that poor implementation, institutional resistance and vested interests have played a role in impeding the FBR’s revenue collection efforts; but, the main issue for the FBR—and the government—is that their strategy itself is wrong.

The FBR’s efforts to widen the tax net, by squeezing the current tax base and attempting to expand it through expensive initiatives targeting the informal sector, is both a waste of money and a distraction from the real economic reform work that the government should be doing. There is far more to gain by enabling individuals and businesses to prosper and increase their earnings, than by imposing extractive taxes today and choking off future growth.

Misunderstanding the Problem

The common refrain, routinely echoed by economic advisors and commentators alike, is that Pakistan has a narrow tax base and the FBR needs to work to broaden it.

One part of this diagnosis is based on the fact that there are specific sectors, such as agriculture and real estate, which enjoy unfair tax exemptions and concessions. Certainly, a sector as economically significant as agriculture—which represents a quarter of gross domestic product and 40% of employment—should be brought into the federal tax net. This, however, is a matter of federal government legislation and tax enforcement; no amount of FBR reforms can broaden the tax base to include agriculture until the feudal landowners sitting in parliament legislate it.

The second part of this assessment is based on the pervasive view that there is extensive tax evasion in Pakistan. The government’s efforts to digitise as much of the economy as possible is predicated on the belief that there are numerous individuals and businesses evading paying all or a portion of their fair share of tax by operating in the informal, undocumented economy.

Trying to broaden the tax base by attempting to force into the tax net economic sectors that are inherently informal and subscale is not the answer.

The FBR’s diatribe against tax evasion by the informal and undocumented sectors is a bit of a red herring. It is true that Pakistan has a large informal economy: World Economics estimates that a third of Pakistan’s GDP is undocumented and thus not part of the tax net. This mostly comprises small, subscale businesses and individuals working without much in the way of a legal, regulatory, or economic safety net. They may be underpaying on their due taxes, but the absolute values of revenue foregone will be little more than a rounding error for the FBR.

The presence of a shadow economy should not be conflated with illicit activity or deliberate attempts to evade taxes. Undocumented and informal economic activity is common across all countries. Brazil, Russia and Thailand—all economies more advanced than Pakistan—have much larger shadow economies both in absolute terms and as a percentage of official GDP. Trying to broaden the tax base by attempting to force into the tax net economic sectors that are inherently informal and subscale is not the answer.

There are no doubt many powerful and influential individuals who manage to evade taxes by using their connections to avoid scrutiny and compliance; they are unlikely to be doing so under the shadow of the informal economy. The powerful and connected do it brazenly. Former FBR Chairman Shabbar Zaidi once recounted in a television interview how he was pressured by the foreign minister—of a government that rode to power on an anti-corruption banner—to withdraw a tax notice against a large Multan landowner. It is this type of tax evasion that makes a measurable difference.

Digging up a Mountain

One of the FBR’s annual performance goals is to broaden the tax base by increasing the number of active taxpayers each year. This is misguided. More active taxpayers will do nothing to broaden the tax base unless they are also earning enough to meaningfully contribute to the exchequer.

At 4% of the adult population, the number of active taxpayers in Pakistan is indeed objectively low compared to other countries. But the figure does not mean much on its own—there is only a weak correlation between tax revenue and the percentage of the population that files taxes. The number of active taxpayers is simply not the best measure of either the breadth or the depth of the tax base.

To encourage more individuals to file their returns, the FBR levied punitively high taxes on the financial transactions of non-filers. The application of differential tax rates imposes extra costs on the private enterprises who are required to enforce them, creating an economic burden for limited gain. Although the FBR managed to increase active taxpayers from 2.7 million in 2018 to 4.7 million by the end of 2024, the new taxpayers contributed a negligible amount to additional tax revenue. Almost all of revenue growth in recent years has come from existing taxpayers.

The FBR is also not efficient at collecting tax themselves. The real tax collection expenditure is borne by the private sector; a bit over 60% of the FBR’s direct tax collection comes from withholding tax, which private businesses collect and deposit on behalf of the agency, at their own expense.

Much of the rest comes from advance tax and payments made at the time of filing, most of which taxpayers do voluntarily. Only 3%, or Rs. 127 billion, comes from collections made on the basis of demand raised by the FBR. Yet the FBR employs a 28,000 strong workforce and spends upwards of Rs. 32 billion in operational expenses to collect this paltry amount.

Browbeating citizens into filing tax returns and spending billions on field units to harass and chase down marginal taxpayers may not be the best approach to growing revenue. What if the government sought to grow revenue not by chasing small traders, but by providing them with the infrastructure to grow?

The multiplier effects from investing in economic growth, through ease of doing business and less government heavy-handedness, dramatically outweigh the meagre short-term revenue gains from building a surveillance state with arrest powers for tax officials.

Follow the Money

Since his appointment a year ago, FBR Chairman Rashid Mahmood has repeatedly stressed that his focus is on the top 5% of earners, whom he has accused of evading taxes to the tune of Rs. 1.6 trillion, or 15% of the FBR’s total tax collection last year. If there is tangible evidence to support this claim, he has not made this public, despite having made this pronouncement on multiple occasions.

The most recent granular tax data published by the FBR is from 2018, when the number of registered taxpayers was substantially lower than it is today. Yet even this data is instructive in showcasing how the Chairman might be drawing the wrong conclusions.

Corporate income tax payments are by far the largest contributor to direct taxes collected by the FBR—representing just under two-thirds of revenue in 2018, and about 75% in 2024. Of the nearly 45,000 businesses that filed taxes that year, just 85 companies accounted for more than half the corporate tax collected. All but one were publicly listed companies or private subsidiaries of multi-national enterprises. Large, established companies are the real engines of revenue growth.

Tax contribution is similarly concentrated among individuals as well; the top 5% of earners, who mostly comprise the shareholders or the salaried employees of the top earning corporations, contribute more than 80% of tax collected from individuals. There are no surprises among the names of the top taxpayers, corporate or individual—the only noteworthy observation is the near absence of any parliamentarian from this list.

The FBR Chairman is right to focus on the top 5%, but his takeaway is completely wrong. Rather than hounding the top 5%, accusing them of tax theft, and attempting to extract ever more from them, what the government should be focused on is enabling the top 5% to grow, both in numbers and in total earnings. Pakistan needs to make the pie bigger, by creating more businesses and supporting them so that they grow larger, pay more in tax, employ more people and pay them well.

The small taxpayers and low earners should be helped by the FBR, not harassed. There is very little for the government to gain by chasing these taxpayers and auditing their returns. Even doubling the tax collection from the bottom 75% will not contribute enough to offset the FBR’s cost of collection.

The FBR should be facilitating small taxpayers in submitting their returns. Despite the FBR’s self-congratulations on “automating 100% of tax filing processes,” anyone who has attempted to use their impenetrably difficult IRIS tax-filing portal knows that it is nearly impossible to correctly file taxes without hiring a tax consultant.

Rather than hounding the top 5%, accusing them of tax theft, and attempting to extract ever more from them, what the government should be focused on is enabling the top 5% to grow, both in numbers and in total earnings. Pakistan needs to make the pie bigger, by creating more businesses and supporting them so that they grow larger, pay more in tax, employ more people and pay them well.

In 2024, 3.4 million individual taxpayers, including 2.3 million who did not owe the government any tax, collectively paid an estimated Rs. 17 billion—more than half the FBR’s operating budget—to accountancy firms and tax advisors to help them submit their tax returns. This is revenue that could have come to the FBR if they actively facilitated taxpayers in filing returns, instead of treating them like potential tax frauds.

The multiplier effects from investing in economic growth, through ease of doing business and less government heavy-handedness, dramatically outweigh the meagre short-term revenue gains from building a surveillance state with arrest powers for tax officials.

Once income and assets reach a certain scale, formalising becomes a necessity. For any legitimate business, beyond a certain point, the savings from tax evasion, under-invoicing and cash dealing cease to stack up when measured against the costs of inefficiency, cash handling, bribes and payoffs. Moreover, large businesses require access to affordable credit lines and flexible trade instruments to operate along with term financing to grow and maintain their competitiveness. All of this requires being able to show strong cash flows and mortgageable assets, which necessitates being fully documented and formalised.

Individual taxpayers also conform to a similar paradigm. There is only so much money wealthy individuals will be willing to stuff into their mattress. High earners tend to want to make productive and diversified investments to grow their wealth. This should be encouraged and more avenues for investment should be created. Harassing taxpayers and making extortionate collection demands will only serve to keep organisations informal and subscale, hurting both the economy and the exchequer.

Focus on the Economy

As the routine affirmations by each successive government on the need for ‘systemic reforms’ and ‘structural change’ indicate, there is only so much the FBR can do on a standalone basis to improve tax collection.

A whole-of-government approach is needed, beginning with a mindset shift towards facilitation and enablement of private businesses rather than suspicion and extortionist scrutiny.

The sooner the government recognises that they need to promote prosperity, not punish it, the sooner they can start seeing real revenue growth. Till then, the FBR, and its Chairman, will continue to face unrealistic revenue pressure, and they will keep passing it on to taxpayers.