Some decades ago, the Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe urged Japanese literature to take upon itself a task: that of remembering, of forever reckoning with the unprecedented, cataclysmic levels of destruction wrought upon Hiroshima. In the war, many other Japanese cities had been incinerated by napalm—in fact, over 100,000 civilians were killed in just two days of bombing in Tokyo alone. But these other cities recovered; most of their populations survived. Even Nagasaki, with its more mountainous topography, had large sections that survived the explosion of the atomic bombing unscathed. It was Hiroshima alone that, in seconds, was eviscerated. Over half its entire citizenry was lost with such thunderous spontaneity that although Nagasaki too had been bombed, the New Yorker journalist, John Hersey, titled his famous aggregation of various witness testimonials of the atomic bombings in 1946 simply, Hiroshima; Kenzaburo Oe called his own series of reflections on the bombs and their victims in 1965, Hiroshima Notes. Remembering what happened in Hiroshima, Oe believed, would be Japan’s obligation to the world, to all humanity; to memorialise this violence in a way such that it would never be repeated.

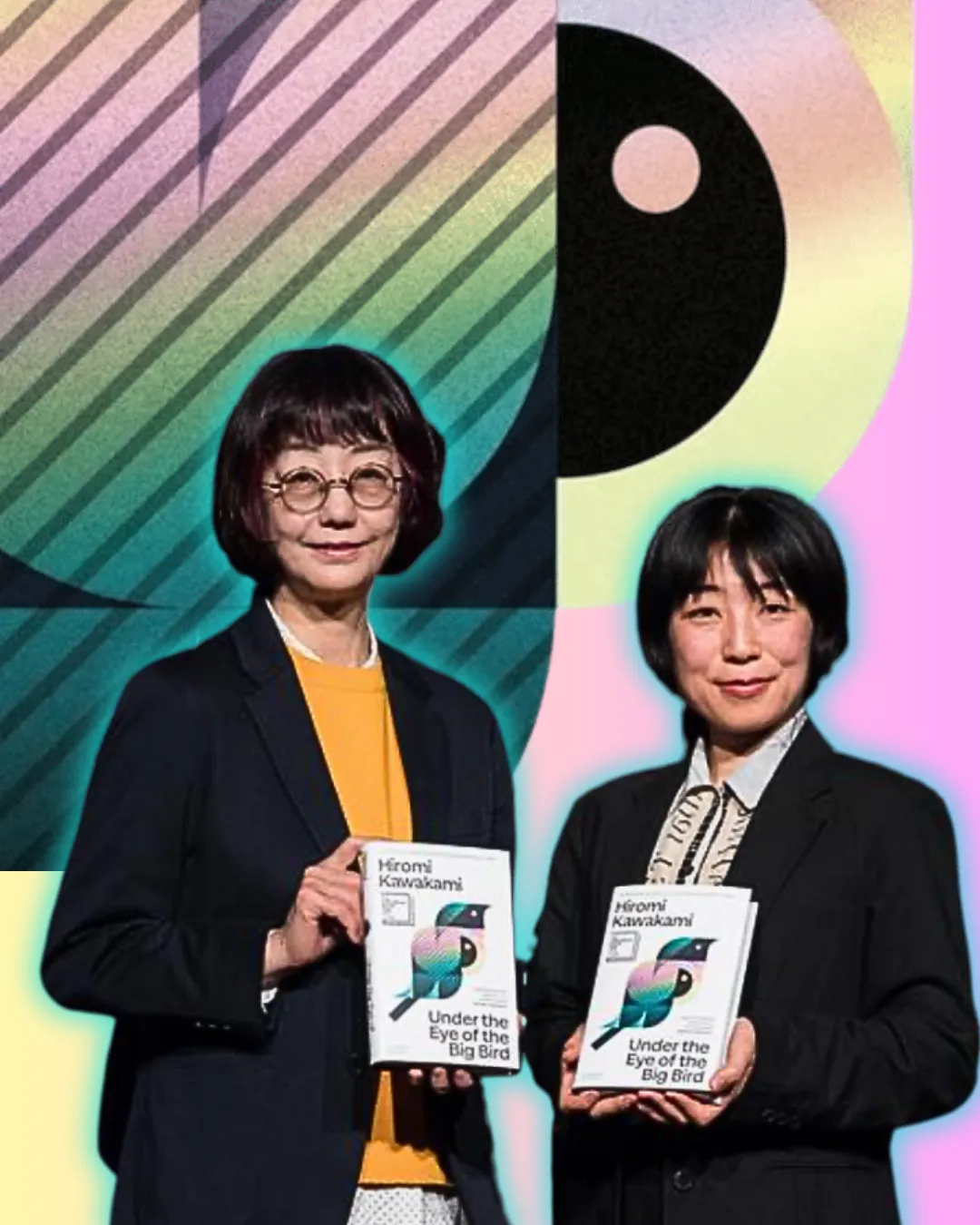

In the years since—in novels, in films, in anime and manga, in children’s programming and in video games—several Japanese creatives have risen to Oe’s calling, producing a range of dystopic literatures that anticipate many horrible apocalypses: technological, ecological, biological, nuclear. Many have received international acclaim. In fact, just a few years prior to the English translation of Hiromi Kawakami’s Under the Eye of the Big Bird, the novelist Yoko Tawada received a National Book Award for The Last Children of Tokyo. This was a short novel, a nightmarish imagining of a future in which children are born brittle, their lifespans fleeting, while the adults around them live uncannily long lives.

For a work that engages with several concepts of higher science fiction, Kawakami is also successful at balancing these headier concerns with the stories and lives of her characters. Many have heartfelt yearnings, unique psychologies; others have very distinctive voices, their own turns of phrase.

In that work, Tawada ensnares her reader in a strange and singular hypnosis. Given how recent this achievement was, that yet one more Japanese novelist was inviting her readers to indulge in another apocalyptic speculation made me uninterested in the project of Hiromi Kawakami, in what I understood Under the Eye of the Big Bird to be.

However, Kawakami surprises on many fronts. First, in form: this text is a novel, but is structured as a collection of short stories. Each chapter is largely self-enclosed, and although taking place in the same fictional universe, it is one that unfolds on different continents, in different colonies, around different manners of human civilisation—aeons can pass from one story to the other. This gives the text a dizzying, chilling scale, and an understated but ever-accumulating sense of mystery about what exactly the parameters are for the world Kawakami creates. The mechanics and ‘rules’, though, are largely withheld from the reader, especially earlier within the novel. This choice greatly enhances the undercurrent of horror in the storytelling, which itself leans not on gore or more conventional sources of danger and suspense, but in quiet, unsettling sentences. Like this one from the first of Kawakami’s many narrators: “While my husband goes to work, I raise children”.

It is only slightly off-beat, only somewhat an unusual formulation—something that suggests rather than announces the presence of the amiss. And it is one among many hair-raising, uneasy moments in Kawakami’s novel that trail behind the reader’s journey of discovering what has happened to the Earth.

Among apocalyptic novels, the breadth of Kawakami’s undertaking is unique. There are other dystopias that have engaged with a fictional crisis from a sociological perspective, or by assembling various viewpoints and stringing together a series of character accounts. Only Kawakami’s is quite as planetary, as humanistic on such an elevated level. Although contemporary geopolitical and cultural distinctions appear, these differences are not dialled up; her text resists banal internationalism. In some stories, characters take dips in hot springs, are named ‘Miss Chiaki’ or ‘Miss Ikuko’; in others, there can be an ‘O’Neal’, an ‘Emma’, people who say words like ‘girlie’ and ‘nice!’; in the remarkable The Miracle Worker, Kawakami imagines a corner of the world seemingly influenced by whatever she has read of Baghdad or Damascus, constructing a small ‘sector’ (to use a term of the novel) in which a prophetess is born. Impressively, none of these contexts are mired by the hackneyed orientalisms one associates with science fiction and fantasy in which different cultures appear, grounding the novel and its various worlds as a study of humanity from an understated, humble lens.

For a work that engages with several concepts of higher science fiction, Kawakami is also successful at balancing these headier concerns with the stories and lives of her characters. Many have heartfelt yearnings, unique psychologies; others have very distinctive voices, their own turns of phrase. Some are even hovercraft pilots, much like the eponymous heroine of the Studio Ghibli film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. They are all, however, swallowed up in the sweep of the novel, in its leaps through time. Their arcs—of friendship, love, motherhood, even of pursuing mothers—are contained in their sections, with denouements and developed plots. But they are always only small, brief pieces of a larger puzzle. Although I am not a reader of mysteries or science fiction, I did think this execution was masterful, even moving in its sparseness. This sparseness is what makes this novel evoke disasters that level and vaporise human lives as indiscriminately as Hiroshima; that situates this text in an existing, extraordinary dystopic tradition.

I had actually hoped I would not appreciate this work. Much like the rest of the Anglophone world, there is already a deluge of Japanese literature in translation sold in Pakistan. I would even suggest that from Gilgit to Quetta, from Lahore to Karachi, it may be easier to spot a Murakami novel in a bookstore than it would be to find any book of Urdu literature’s foremost surrealist, Naiyer Masud. Yet for all this consumption of Murakami (either pirated or otherwise) and of other contemporary authors from Japan, there is very little to show in terms of tangible impacts this literary engagement has resulted in for creative arts across Pakistan.

If there have not been such developments—although Mohsin Hamid has once cited Murakami as an influence—one wonders about this culture of consuming Japanese literature at the unsaid expense of others. Translations like Under the Eye of the Big Bird have been commercially successful, particularly in Pakistan’s upmarket bookstore chains. However, if all this culture amounts to is a pleasurable, foreign, exotic escape through a novel, is this range of reading only to the end of cultivating a juvenile, unmoored niche? It is worth noting that no translator of Murakami, Mieko Kawakami, Tawada, or any number of contemporary Japanese authors has attended literary festivals in Lahore or Karachi. More damningly, only the translator of Sayaka Murata, Ginny Tapley Takemori, has participated in a call for a ceasefire in Gaza. The translator of Under the Eye of the Big Bird, Asa Yoneda, is a lecturer of Japanese translation in the United States. Even she has not participated in any academic calls for boycotting Israel, signed any of the famous statements of solidarity with that country’s encampment protests, or participated in calls for a ceasefire in Gaza. And in spite of an international outcry, Murakami accepted a literary prize in Israel back in 2009. One must therefore ask: is Japan a proximate ‘Other’, or is it just as politically and ideologically foreign as the United States?

This is not to say there is nothing to learn from this literature. I can imagine concentrated efforts to grapple with the lonely narrators of Mieko Kawakami, and the light-hearted stories of Banana Yoshimoto might be very productive for fiction in Pakistan (Asa Yoneda has also translated a very wholesome Yoshimoto collection called Dead-End Memories). Haiku translations of the 18th century Basho have also emerged (and been reprinted) in Urdu and Punjabi. But the ability to intelligently navigate this poetics is also more possible for those who are familiar with the history and dynamics this world is putting itself in conversation with, and I am not sure that there are any university departments in Pakistan offering the academic studies that might supplement this literary engagement. That the praise of a recent anime release in Pakistan surrounds the novelty of its form—rather than to commend its storytelling—may be because its creators have only grasped at limited pleasures of Miyazaki’s work. One cannot blame them for their oversights. But one can advocate for a serious disengagement with this literary world and a greater focus on writers like Banu Mushtaq and Naiyer Masud, or the authors of Arabic, Persian, and Black African literary worlds. I am sure these other fictions will leave more meaningful, tangible impressions on readers in Pakistan.

Yet for all this consumption of Murakami (either pirated or otherwise) and of other contemporary authors from Japan, there is very little to show in terms of tangible impacts this literary engagement has resulted in for creative arts across Pakistan.

Yet, begrudgingly, I must admit that Under the Eye of the Big Bird is a pertinent novel. For many readers who fear imminent nuclear holocaust, who worry about glacial outbursts and animal extinctions, it will be a depressing and fascinating text; the author says she began it when she watched the news of the radiation leak in Fukushima in 2011, when she was thinking again of Hiroshima. As the possibility of other Hiroshimas happening within our own life-times has only increased, as such threats have been so brazenly made to the people of Tehran, Hiromi Kawakami’s is a powerful and fresh addition to a Japanese imagining of the apocalypse, displaying the potential of speculative literature at its very height. Perhaps it is only those from the country of Hiroshima who can achieve these imaginings as carefully and as cerebrally as does Under the Eye of the Big Bird.