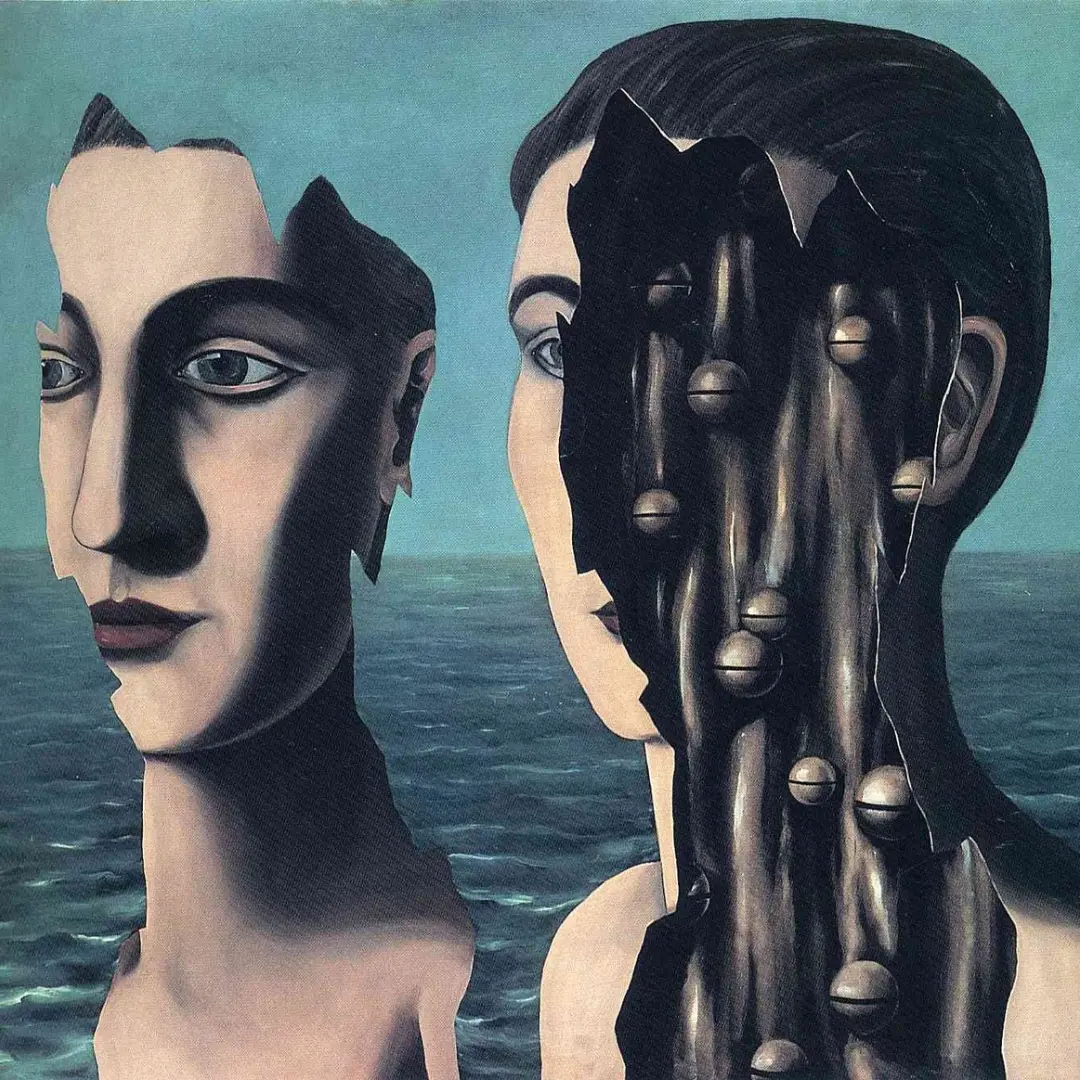

Earlier this year, I came across and read Dostoevsky’s The Double, a short novel that threw me off balance. It is not as sprawling or renowned as his later works, but it carries a distinct dread. A dread not of violence or ruin, but of gradual erasure. A dread that feels uncomfortably close.

Published in 1846, The Double is one of Dostoevsky’s earliest attempts to engage with the modern subject. It tells the story of Yakov Petrovich Golyadkin, a low-ranking civil servant in St. Petersburg, who lives a modest, almost invisible life. He is polite, self-effacing and terribly anxious about being seen. One night, after a humiliating social incident, he encounters a man who looks exactly like him. This double, at first affable and charming, begins to take over his life. He does so not with force, but with fluency. The double moves easily where Golyadkin stumbles. He smiles where Golyadkin hesitates. Soon, the original is pushed to the margins of his own existence.

Dostoevsky never resolves the double’s nature. “The nocturnal visitor was no other than himself... absolutely the same as himself — in fact, what is called a double in every respect”. This ambiguity is not a flaw. It is the very centre of the novel’s brilliance. The double is not a ghost or an illusion. He is a mirror held up to a man who cannot perform the rituals of the city. He is the shape one must assume to be accepted or the punishment for failing to do so.

This is not just a story of madness. It is a story of modernity, a modernity that demands the division of the self. One part must smile, adapt, fit in. The other part must carry the weight of confusion, fear and doubt. The double is not an illusion; he is built into the city’s design. He is the grammar of urban life.

Golyadkin knows this. He tries to explain himself in broken phrases that reveal his isolation. “I’m a simple person, and not ingenious, and I’ve no external polish. On that side I surrender... I lay down my arms”. He tries to convince his doctor that he is humble, harmless and uninterested in the intrigues of fashionable life. But the city does not reward humility, it rewards performance. And the double performs better.

This is not just a story of madness. It is a story of modernity, a modernity that demands the division of the self. One part must smile, adapt, fit in. The other part must carry the weight of confusion, fear and doubt. The double is not an illusion; he is built into the city’s design. He is the grammar of urban life.

There is a moment in the novel when Golyadkin watches his double being admired by society. The scene is grotesque. “Everyone was exalting him... putting the real and innocent Mr. Golyadkin to shame... and showering blows on the man so well known for his love towards his fellow creatures”. The city chooses not the man who is kind or sincere, but the one who can play along. The one who knows how to flatter, how to dance, how to disappear into the ritual.

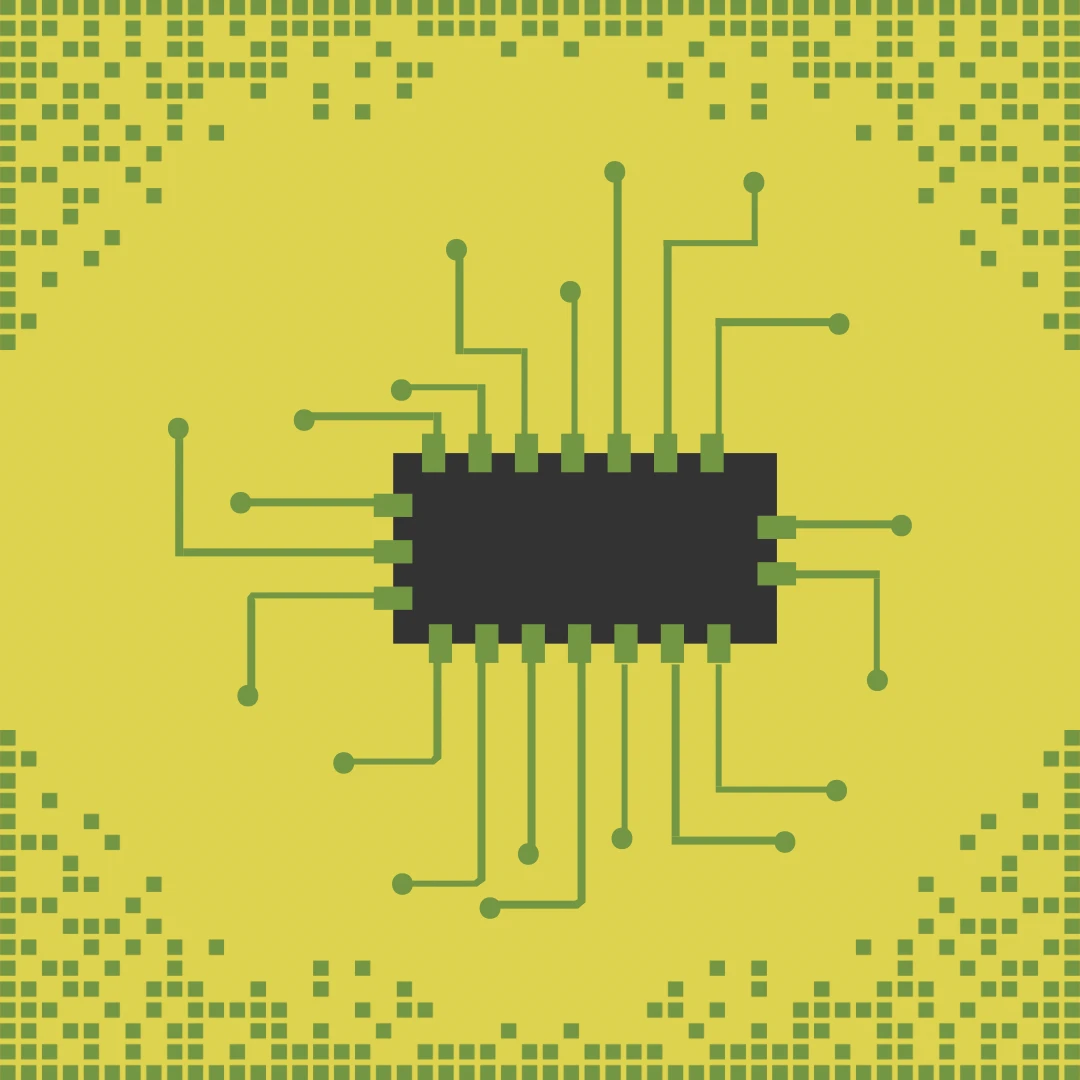

Reading this, I could not help but think of our own cities, especially the more ‘important’ urban centres — Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad — where the self must constantly shift between registers: between the formal tongue and the native one, between respectability and survival, between what we are and what we must pretend to be. These cities, in their planning and aspiration, imitate the Western metropolis. They speak the language of growth, order and civility. They do so, however, without the organic histories that gave that language shape. So, the mimicry becomes severe and violent.

We see it in the rise of glass towers next to informal settlements, in the spread of CCTV and biometric attendance systems, in the way our streets make no space for pause, in how the poor must smile to be tolerated and the middle class must erase its own textures to be visible. The city no longer asks who you are, it asks how well you perform.

We are all, in one way or another, Golyadkin. We whisper to ourselves: “I am all right... I am quite like everyone else”. We try to stay quiet, not disturb the choreography. But silence is not enough. Eventually, a version of us appears — younger, more fluent, more legible. And it begins to replace us.

There is something of the flâneur in Golyadkin. But unlike Baudelaire’s wandering observer, he is not detached. He is devoured. He wants to belong. And that is what destroys him. The city demands a mask — and when Golyadkin’s mask slips, the city sends the doctor.

The final scene is quiet, almost ceremonial. The doctor, Rutenspitz, arrives. He takes Golyadkin’s hand: “He had seen him very often, had seen him that day...” and now he draws him away. Golyadkin does not resist, he simply follows. The system has no need to punish; it only needs to file away the unfit.

This is not just the story of one man; it is a structure that repeats. Pakistani cities, like their imperial predecessors, now operate on the same logic: they sort people by fluency, by accent, by polish. They want efficiency, not presence, aspiration, not reflection. They create a stage, and those who cannot act are asked to exit.

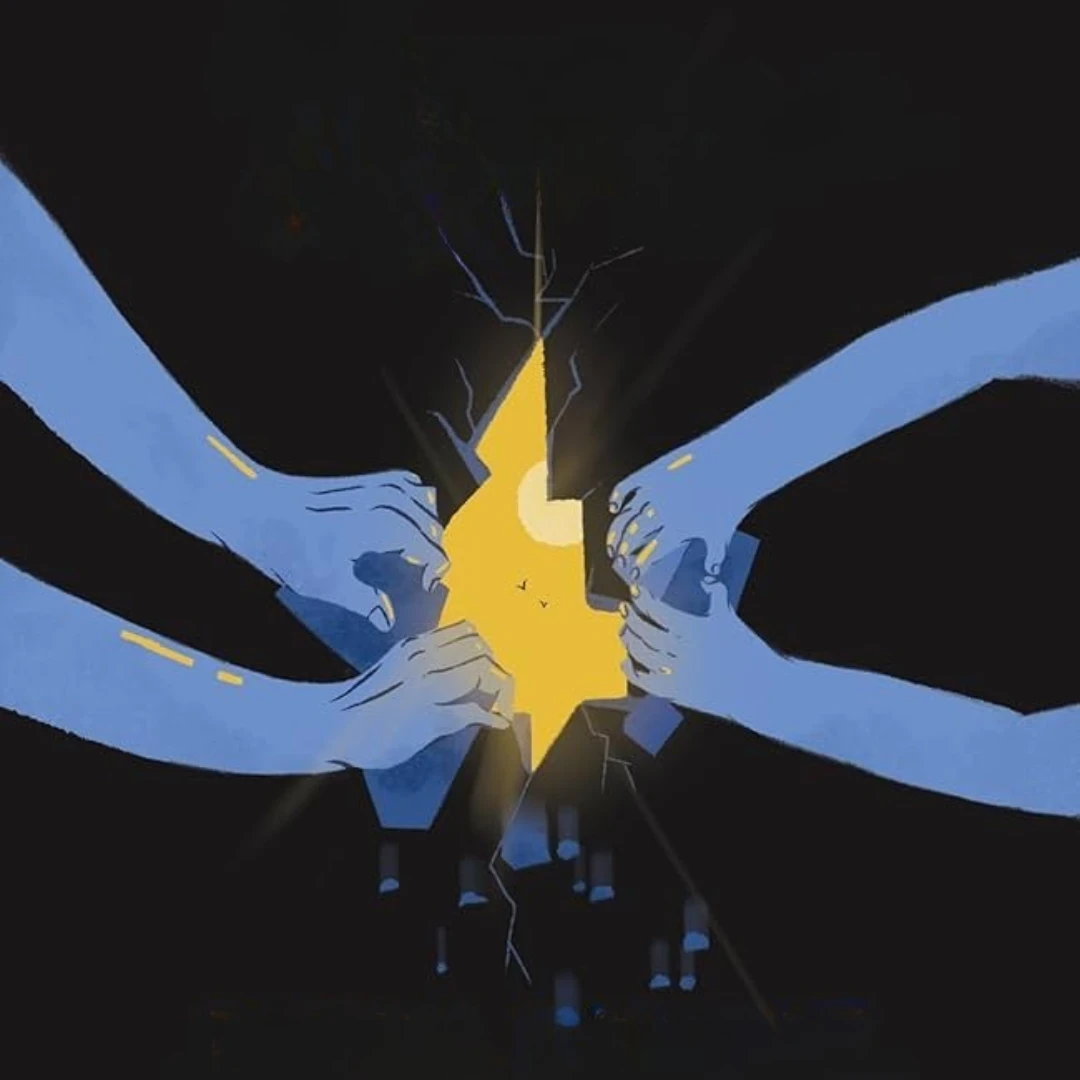

Dostoevsky saw this long before it took global shape. His genius was not in the invention of the plot. It was in the ability to name a condition, a condition where the self begins to fracture, not under madness, but under too much mimicry. T. S. Eliot’s Prufrock said, “There will be time... to prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet”. In The Double, we see what happens when the face prepared becomes the only one visible. And the real one, confused and breathless, is led away in silence.

In cities built on borrowed dreams, this is the cost of becoming ‘modern’. To survive, one must split. To belong, one must vanish. The novel leaves us with a single question. One that echoes in every office corridor, every gated enclave, every closed-off park.

How many selves must one carry to be seen as one?