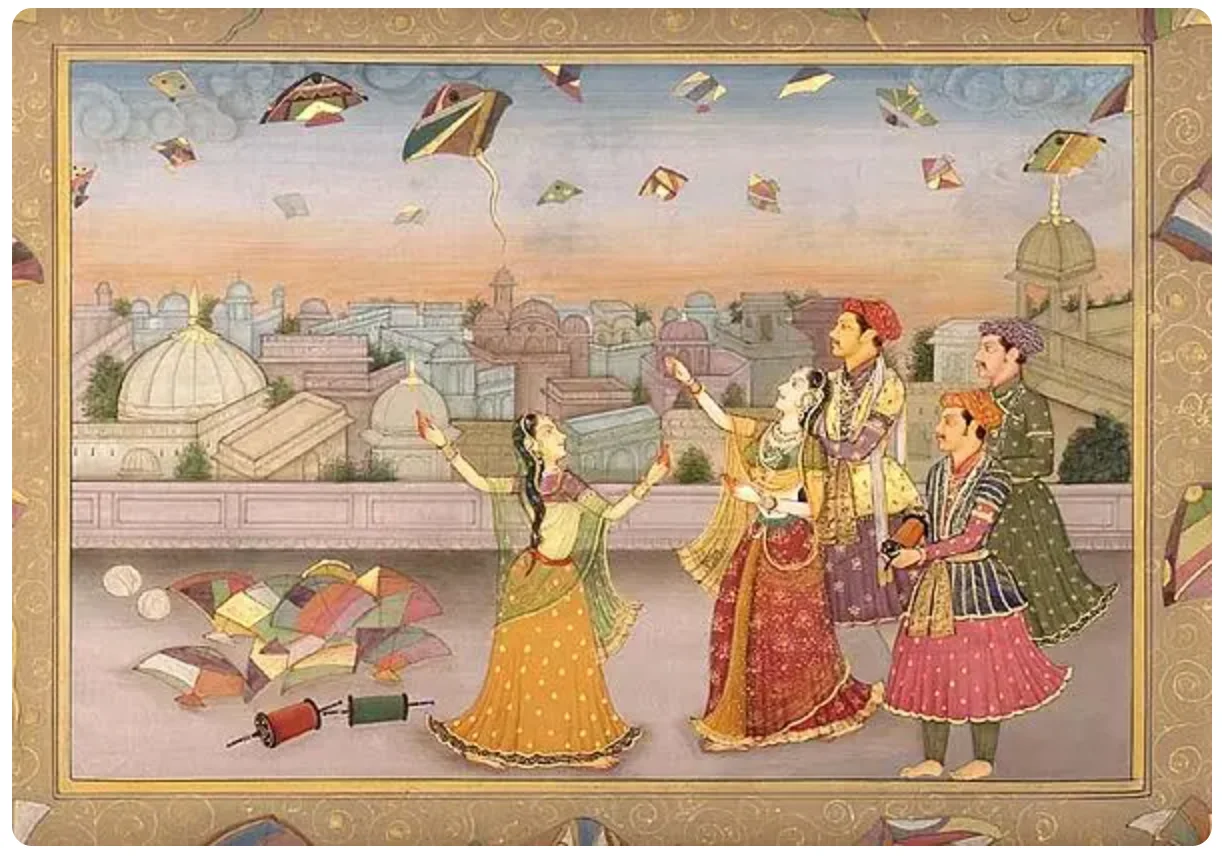

Before my parents married, all my mother knew of my father was that he loved flying kites. In the days before the wedding, her brothers teased her relentlessly with off-key renditions of Fariha Pervez’s iconic 2000s Basant anthem Patang Baaz Sajna. Watching its grainy video on YouTube this morning, I am swept back to a city I recall only in fragments, of men and women leaning over narrow rooftops, faces tipped upward, and kites, so many kites — magenta, chartreuse, marigold — scattered across a bluish-grey sky.

Before it was the dwindling smog that announced spring’s knuckles against the doors of this city, it was Basant. For many who grew up in Lahore, kite-flying presented a rare form of collective orientation and loosening of ordinary rhythms that united this city of poets, saints and lovers like little else. Archives from the time show dhols, fingers sticky with deep fried sweets and people congregating to watch whose kite would soar the highest, stretch the widest, and, most importantly, stay aloft the longest. My own memories are simpler, sitting on the stairs leading up to the roof of my grandmother’s house, a cold glass of Rooh Afza in hand, counting kites. Ten, then eleven, then twelve, then eleven again.

The word Basant comes from the Sanskrit vasanta, which means spring, the season of sarson ke phool, and a time of celebration in Punjab, where agriculture has long given form to both labour and leisure. Historians sometimes connect Basant’s presence in the subcontinent to Sufi traditions. One oft-repeated story returns us to the fourteenth century, to Amir Khusro and his beloved teacher, Nizamuddin Auliya, who had retreated into grief after the death of his nephew.

In Lahore, Basant was consolidated under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who transformed it into a grand fair and brought kite-flying into the fold of nineteenth-century festivals, especially those at Sufi shrines. Accounts of the time describe Ranjit Singh and his wife Moran Sarkar clad in yellow, flying kites themselves.

One day, wandering near a khanqah at Chilla, Khusro came upon village women draped in bright yellow, arms brimming with mustard flowers, singing and clapping as they made their way to the temple in celebration of spring. Struck by their unguarded joy, he returned in a yellow sari and body strewn with flowers, and sang before Nizamuddin Auliya. The sight startled the saint into a smile.

Whether apocryphal or not, this story, so far from us, persists because it represents what is true of Basant — that joy itself can be a form of reverence, that celebration belongs as much to the sacred as to the everyday. Each year, the fakirs at Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya Dargah in Delhi gather to greet spring with yellow flowers and raags.

In Lahore, Basant was consolidated under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who transformed it into a grand fair and brought kite-flying into the fold of nineteenth-century festivals, especially those at Sufi shrines. Accounts of the time describe Ranjit Singh and his wife Moran Sarkar clad in yellow, flying kites themselves. His Basant darbar stretched over ten days, featuring displays of martial skill, all in the season’s signature colour. From there, kite-flying spread rapidly across Punjab, with Lahore firmly established as its centre.

Traditionally held on the first Friday of February, the festival was sometimes shifted to avoid the holy months of Ramzan or Muharram. For a brief moment each year, Basant levelled the city. All that was needed to participate was a patch of sky and a spool of string. Shopkeepers flew kites beside factory workers, children beside elders and students beside teachers. Hierarchies dissolved, and in the open air, only skill counted. One sharp cut would send a kite drifting over rooftops, to be claimed by the swiftest hands.

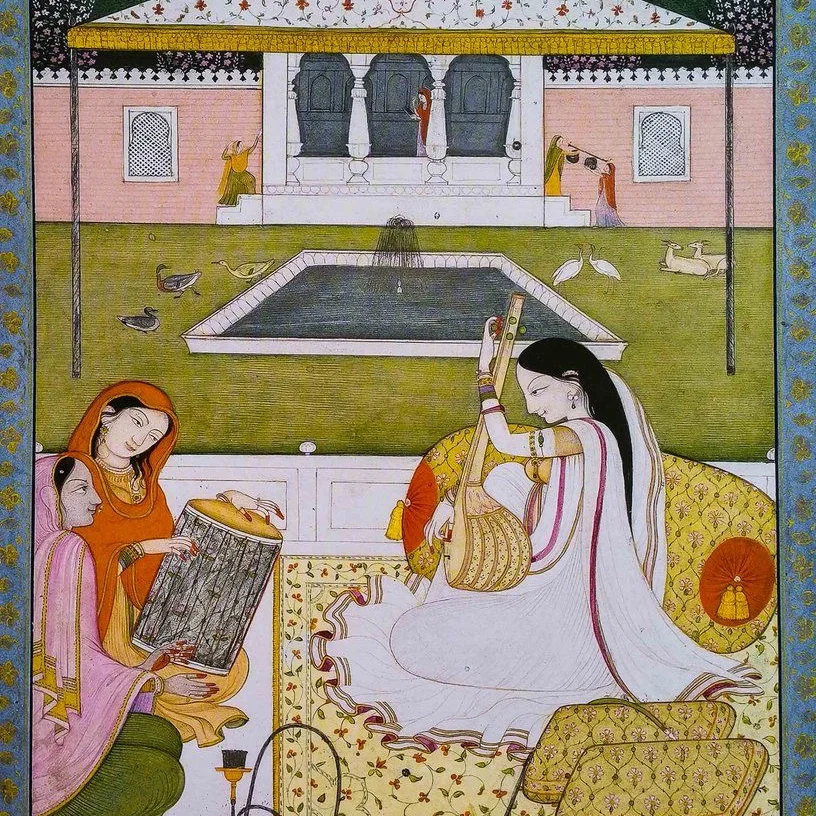

In the Walled City, kite-flying and kite-fighting especially, extended well beyond the festival. By the 1980s, informal crews had begun to organise themselves around skilled mentors, ustads, and turned their competition into an apprenticeship. All of this depended on a distributed network of labour. Kites required skilled makers — men, and increasingly women — trained in cutting guddi paper, balancing bamboo spars, mixing glue and coating string. During my undergraduate research, I spent time with kite-makers throughout the Walled City, many of whom had inherited the craft through familial lines.

From what I learned, kite-making was a kind of embodied wisdom, passed through shared practice. The craft moved from hand to hand, as gestures became second nature, fingers grasped the tension of paper and eyes measured proportion by feel alone. Such expertise survived through repetition, as each winter’s preparations refreshed the memory stored in movement and touch. Basant gave the craft continuity. Without the festival, the skills, and those who held them, lost the avenue for their work, eroding both the craft and the identities bound to it. Yet, for many, kite-making was part of a larger story of belonging and meaning, and never just a way to earn a livelihood.

Often overlooked in nostalgic accounts of Basant is the extent of women’s participation in its home-based industry. Kite-making was a patchwork effort, with one household assembling the guddi, another the kuman, another the tir, and yet another the jor. Even the architecture reflected this labour, with recessed wall slabs built inside homes to shelter kites from light and damp.

Near Taxali Gate, I met an ustad in his seventies. We sat cross-legged on a carpet while his granddaughter passed chai and biscuits through a small partition. He recounted how, as a boy, he pieced together scraps from fallen kites he had run after through winding streets. Where most people take an hour to make a kite, he could do it in half that time. Over the years, honing his craft had led him to teach more than a hundred others in his community.

Basant had influenced his life as deeply as the craft itself. His WhatsApp was overflowing with videos from kite-fliers on both sides of the border. He insisted that wherever kites fly in the world, a Lahori leads the way. Near the end of our conversation, he turned his palms upward, sketching the lines with his finger. “In mein se kuch lakeerain Allah ne di,” he said, “aur kuch patang baazi ne” [Some of these lines were given by God, some by kite-flying].

Another man I met, who used to be the owner of a kite shop, was known to everyone as Billu. As a child, he had been famous for chasing fallen kites by climbing walls and trees like a cat to retrieve the most elusive ones. That is how he had begun his collection. Now, with the kites gone and his days spent in an office, the name was all that remained.

Until the late twentieth century, Basant used to be observed with relatively little state intervention. In the 1990s, however, a renewed effort to brand Lahore as Punjab’s cultural capital brought government promotion, corporate sponsorship and multi-national investment. With such scale came transformation, and the kites grew larger, while the dor was refined for durability. What went largely unregulated was the danger this produced. Glass-coated manja grew sharper and deadlier. Combined with denser power lines, heavier traffic and a swelling population, these changes posed serious risks to public safety, especially for motorcyclists.

When authorities moved to ban Basant in the mid-2000s, the decision was justified as a response to mounting fatalities caused by falls, electrocution and increasingly lethal kite string. At the same time, certain groups began to reframe the festival as non-Islamic, casting it instead as essentially Hindu, a narrative amplified by a wave of polemical publications between 2004 and 2010. Underlying these debates, however, was a widespread and genuine fear that the festival’s altered material conditions had made it dangerous in ways the city could no longer afford.

Often overlooked in nostalgic accounts of Basant is the extent of women’s participation in its home-based industry. Kite-making was a patchwork effort, with one household assembling the guddi, another the kuman, another the tir, and yet another the jor. Even the architecture reflected this labour, with recessed wall slabs built inside homes to shelter kites from light and damp.

Promulgated through a governor’s ordinance, with little input from the communities most entangled in the practice, the prohibition on kite-flying interrupted the chain through which knowledge and connection had passed from one generation to the next. Kite-makers shuttered their workshops and found new trades, while home-based production slipped underground for export. Children grew up never learning to wind a spool, and as modernisation accelerated, the city’s ways of living and of experiencing joy shifted.

This year, preparations are once again underway to celebrate Basant, now under a tightly regulated framework of permits, designated spaces and surveillance. The language of revival promises return, but return is a misleading word. What is being proposed is not Basant as it once existed — communal, inclusive, excessive, city-wide — but a managed spectacle, which is perhaps the only form compatible with contemporary safety imperatives. Alongside this, however, there must be clarity about the nature of the loss itself, particularly as it relates to the disruption of Basant’s role in sustaining communal traditions and shared expertise across generations.

In such moments, there is a temptation to rush towards redemption and insist that what was taken can be restored. But some losses are irreversible, even when circumstances change. Basant’s absence for nearly two decades has disrupted a dense network of practices, skills and community; in its place, the city has expanded under a new generation. Now, as Basant weekend arrives and the fields turn yellow beneath a widening sky, most of us no longer know what, exactly, to look up for. But this year, perhaps, we can try again.