On a weekend where most of Lahore was on rooftops across the city, I was surprised to find a good portion still at ground level, beneath the colourful bunting at Alhamra for Day 2 of the annual Lahore Literary Festival (LLF). It seemed as if the city was voracious for what it serves best: culture, community, the promise of spring, and of course, literature. The shared theme did not seem to end just at appearances, with the festival insisting on celebrating the region’s cultural heritage across its various offered talks and sessions.

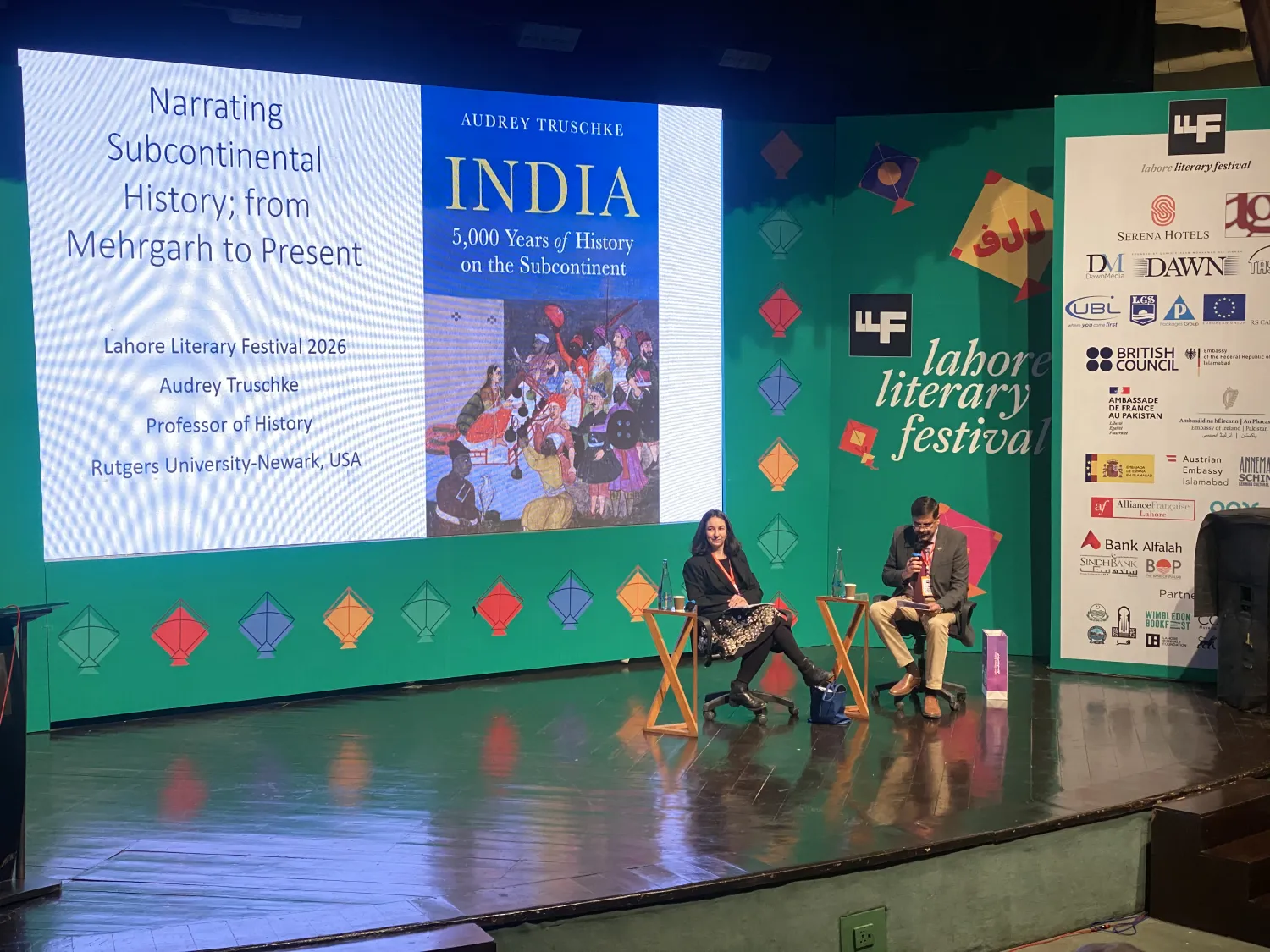

My day at the festival started at 11 am in Hall 2, with Professor Audrey Truschke’s session on her book India: 5,000 Years of History on the Subcontinent. Truschke is a professor of South Asian History at Rutgers and the author of three other acclaimed books — all monographs of Mughal history. Her new book is a ‘sweeping account of five millennia, from the dawn of the Indus Valley Civilisation to the twenty-first century’, and tells the fascinating story of the region historically known as India ― which includes today’s India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and parts of Afghanistan ― and the people who have lived there.

“While the Indus Valley Civilisation is old, the awareness of it is still new,” stated Professor Truschke, initiating the session with a rundown of the region’s history and the structures and systems of the people of the valley that serve as a precedent of civilisation; she also pointed towards the still unexcavated and undocumented areas. Citing Sukkur, or historically what is known as the area of Lokhanjo Daro, the largest city of the Indus Valley Civilisation, she compared it to the accidental discovery (and excavation) of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, followed by a comment about developments via “peak British colonial iconoclasm”... (referring to William Bounton, the British road engineer who ruthlessly dug down the Harappa remains in search of brick ballast for a railway line he was laying from Multan to Lahore).

Truschke also mentioned other historical tidbits from her book in her presentation to whet the audience’s appetite, for instance, how the wildcard concept of Pakistan first arose from a map of India labeled ‘Continent of DINIA and its dependencies’, the history of Hinduism before there ever was a Hindu and a Brahmi inscription from the 3rd century that serves as historical graffiti (‘Captain Vishnudhara of Bharuch was here’ it reads) to name a few.

Although the book covers various political and social movements across the region, while also centring South Asian voices, along with present-day obstacles (climate change being an important one), the focus of the session seemed to lie primarily on the significance of modern-day Pakistan being the cradle of civilisation and the silent erasure of this fact. Whether that was circumstantial or pandering to the present audience, it seemed to be a hit and was followed by an enthusiastic Q&A session.

The second panel of the day had me in the seats of the venerated Hall 1, where writers Mohsin Hamid, Geoff Dyer, Mahvish Ahmed and David Wagner, along with Canadian journalist CM OBE Lyse Doucet (now an author with her debut novel The Finest Hotel in Kabul) spoke of immersive writing and how travel, displacement or reportage shape their writing experiences. The panel was moderated by Roger Crowley, whose familiarity with each of the panellists made for a case of immersion in itself. While each panellist fleshed out their writing journey and what they thought made for immersive writing — Lyce Doucet’s mix of reportage observations and fiction conventions to tell the story of a people while telling the story of a hotel; Mahvish Ahmed’s very intimate yet universal journey of moving countries and nationalities, while navigating womanhood and motherhood; David Wagner’s “Leben” in which he strayed away from his usual stories of cities and instead wrote of his personal time in the hospital for an organ transplant (“Illness is the travel of the poor,” he stated dryly) — the one key takeaway of the panel I thought critical to share was Geoff Dyer’s case of immersive reading making for immersive writing.

“I think, for me, one of the most stunning experiences I’ve had of reading in the last ten years is [reading] Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurty and it put a terrible strain on my marriage, because although I was there in the house with my wife, I wasn’t there at all. I was actually somewhere between Texas and Montana,” he joked. Moreover, he stated that whereas some people seek immersion in worlds and stories, others look for ways inside a writer’s or character’s mind, mentioning authors such as Annie Dillard and Rebecca West whom he admires for this form of immersive writing.

On writing as a way to come back to, or immerse in yourself, Mohsin Hamid made a case for writing being a “conversation with ourselves” and that writing usually allows us to break free from other people’s — as well as our own — perception of ourselves. Identity, or “the tyranny of being trapped in the story we told us about ourselves” is remedied by writing.

Writing as a way to reconnect with one’s self or to re-engage with the past in the future was also something that was briefly approached in Kamila Shamsie’s session The Private Life of Power, where she was in conversation with Jane Marriott, the British High Commissioner to Pakistan, about how politics affects friendships, memory and moral choice. The conversation revolved around her last book, Best of Friends, Karachi and London as the backdrops for her stories and how she finds herself re-engaging with her older books because of the intimate relationship her new and growing readership has with them. She also shared how her ESPN article about Pakistan women’s cricket was the springboard for Best of Friends, and how the changing winds around the time of Benzair Bhutto’s transition to power (in reference to Mandela being freed from prison and the fall of the Berlin Wall) inspired a fervour in both sentiment and action — things happening in the streets of Karachi that hadn’t before, and now how Basant had come back to Lahore — that gave birth to optimism. “[Writing] cannot be despairing. There has to be a sort of optimism in writing,” she said. Shamsie further spoke of her optimism in people, recalling an event where she was caught in a riptide and had not one or two, but seven people come to her rescue. She talked about the innate goodness in people, or something of that sort, that is tainted when encountered by power.

She also commented on her dual-nationality and the various people who leave home for a better life in whatever circumstances, recalling what author Hisham Matar (My Friends) said to her about feeling both like “the betrayer and the betrayed”, where you may seem like you are betraying home by leaving, while home betrays you by stripping you of reasons to stay.

At the book talk for Maha Khan Phillips’ The Museum Detective, a delightful and immersive conversation ensued about the fake mummy case in Karachi 2000 that inspired the book; on the panel was archaeologist Dr Asma Ibrahim, who is currently the founding director of the Museum, Archives and Art Gallery Department for the State Bank of Pakistan and was the reason behind the mummy hoax being uncovered. The talk was moderated by Hassan Tahir Latif (The Aleph Review and Peepul Press). Also present in the audience was Dr Salima Ikram, who, along with Dr Asma, inspired the character of Detective’s protagonist, Gul. Phillips mentioned how both Drs Asma and Salima are “smart women doing incredible things who are not talked about enough” similar to Gul.

I ended the festival day at the second commencement of the Pakistan Youth Poet Laureate; a brilliant hour of Urdu, English and Punjabi poetry from the finest in the country — available in an anthology titled ‘Jashan’, and the declaration of the two new poet laureates: Anas Rehman (Urdu) and Mina Shoaib (English) for the year 2025.

I felt wary when I first realised that the festival dates coincided with those of Basant. Yet walking around Alhamra all day, surrounded by people who seemed in no rush to be anywhere else, it felt like the people of Lahore had unanimously arrived at the decision that the festival was part of the day’s choreography. With its 14th edition, the LLF seems to have solidified itself in the city’s cultural tapestry as a thread that won’t come loose easily.

All photos courtesy of the author.